Blog

Most Recent

Every June, as rainbow flags fill our social media feeds and storefronts, it’s important to remember what and who Pride is really for. Pride is a celebration, yes. But it began as a resistance movement led by bold, visionary leaders, many of whom were Black and Brown trans women and queer people of color.

Sexual Assault Awareness Month may have drawn to a close, but for survivors in our community, the need for safety, healing, and support continues every day.

Each year at the Concealed Revealed Art Auction, we thank, celebrate, and highlight the contributions of our incredible partners and supporters. We’re excited to share this year’s awards! We asked each awardee to share a little about their work and connection to the YWCA Center for Safety and Empowerment.

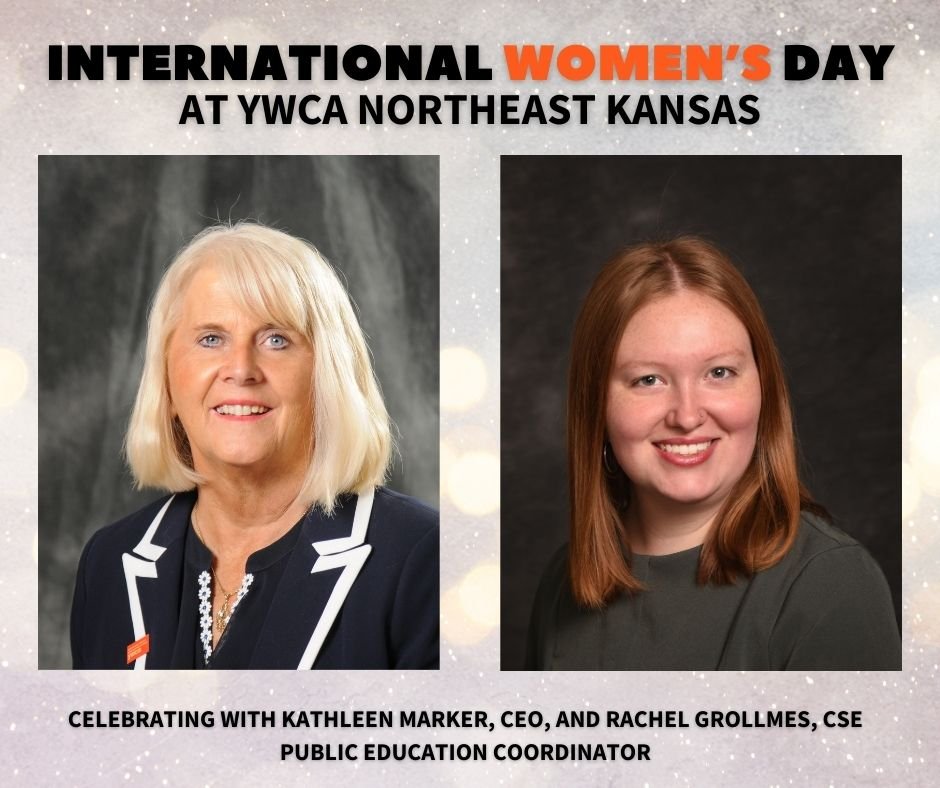

This year, as we mark International Women’s Day, we are reminded of the profound change that is needed—and the bold action required to create a world where dignity, freedom, and equality are for all women, everywhere.

Claire’s Community is a super cool organization that works to end dating violence for all ages. They provide educational resources to learn about consent and healthy relationships!

Get your tickets to the 22nd Annual Concealed Revealed Art Auction, Saturday, April 5. For more than two decades, this event has been supporting the crucial work of the YWCA Center for Safety and Empowerment.

This year, Kansas legislators have an opportunity to increase penalties for commercial sex buying. Learn more about this legislation, and how YWCA and our partners work to support survivors in our community.

Each year, YWCA Northeast Kansas presents an Employer of Excellence Award to a local business or organization that is leading the way in its commitment to its employees and the community it serves. This year’s Employer of Excellence is Envista Federal Credit Union.

The YWCA movement is powered by phenomenal women leaders who uplift us all as they blaze a path toward justice and equity. At this year’s Women of Excellence Awards on September 14, Linda is being honored as the 2024 YWCA Empowered Leader.

At YWCA Northeast Kansas, we believe that survivors' experiences should be centered in our society's response to gender-based violence. We support clemency for Sarah Gonzales-McLinn, and you can take action today in support, too!

Discover how the latest updates at the Center for Safety and Empowerment enhance 24/7 support provided to survivors of sexual and domestic violence, stalking, and human trafficking.

Please join us in welcoming Cheri Faunce as our new CEO! Faunce brings to the organization a long career in public sector and nonprofit leadership, most recently as the Vice President of Development for SparkWheel. She officially starts her role on May 16.

Teachers in our Early Learning Center give their whole hearts and a whole bunch of energy to provide phenomenal care to their students every day. So we’re excited to spend a little time appreciating and honoring them this week!

Our local partners help us move from learning to action, by joining us in efforts to bring the YWCA Racial Justice Challenge topics into our community. Attend the forum on April 30, and follow the Kansas Reflector series.

The YWCA movement is fueled by the determination, courage, and passion of women committed to the work of racial and gender equity. This International Women’s Day, we’re celebrating the YWCA movement by highlighting two of our local leaders - Kathleen Marker, CEO, and Rachel Grollmes, CSE Public Education Coordinator.

The devastating events in Kansas City on Wednesday remind us that gun violence is a real and constant threat to our communities and the people we serve. We remain committed to the work of anti-violence, including building safe communities where women and girls can thrive free from the threat of gun violence.

As we transition from National Human Trafficking Awareness Month into National Teen Dating Violence Awareness and Prevention Month, it’s an ideal time to discuss how parents, guardians, and caring individuals can help keep the youth in our community safe from child trafficking.

This Black History Month, we’re honoring the work of four YWCA sheroes who courageously led the nationwide efforts to bring racial justice to the forefront of the YWCA movement. Thanks to them, YWCA’s long history of Empowering Communities & Advancing Justice continues to move us forward today.

What comes to mind when you think of stalking? Maybe your mind’s eye becomes filled with images of strangers in trench coats, ominously lurking a little too close for comfort. Or perhaps you visualize a big white van driving behind you, taking too many of the same turns.

A recent report from the Polaris Project answering the question, “Where does trafficking occur in the United States?”

The YWCA Advocacy Committee works year-round to create a more just world through advocacy, civic engagement, and community education. Join Us.

Theresa Dodson admittedly didn’t know much about YWCA when she first got involved. But she soon learned just how committed the staff and volunteers are to YWCA’s mission.

Angela Lewis has been #OnAMission with YWCA since college, because she knows the importance of empowering women and girls to thrive.

This year, we announced plans for a CSE shelter expansion that will more than double our capacity once renovations are complete in Spring of 2024. Read on for a sneak peek inside the construction zone!

Tara Wallace is committed to this community, and she joined YWCA Northeast Kansas #OnAMission to build a stronger, more equitable home for everyone to thrive.

Despite recently retiring, Gina Millsap is working as hard as ever to make a difference in our community! She is on a mission with YWCA Northeast Kansas, serving as President of the Board of Directors.

Todd Payne is on a mission with YWCA Northeast Kansas, using his budget and finance expertise to support the organization through serving on the Board of Directors.

Fatima Perez-Luthi is on a mission with YWCA Northeast Kansas, using her leadership skills to advance our work and bring the community together.

Popular perception has long held that domestic violence increases during the holiday times. However, this can perpetuate myths around the root cause of domestic violence.